How one big project changed minds on the causes of heat prostration.

The Boulder Canyon Project, now called the Hoover Dam, was awarded to The Six Companies in the spring of 1931. For many people, work could not commence soon enough. Unemployment exceeded 25 percent, and the hope of landing a job caused individuals to flock to this desolate area on the Arizona-Nevada border. The company planned to begin work in the fall, but President Herbert Hoover insisted they start immediately, just as the mercury was climbing.

The working conditions on the project were brutal. There was no shade, and summertime temperatures exceeded 100 degrees. Some employees could not handle the heat and quit; others tried their best to cope, but it was not easy, as the summers of 1931 and 1932 were fierce, temperature-wise.

Many deaths occurred from heat prostration. Workers who collapsed had cold water tossed on them. If that did not revive them, they were transported to a hospital in Las Vegas. Many would not survive the one-hour journey.

There were several theories about what caused heat-related medical issues and why some people were more susceptible to the heat. These may seem irrational today, highlighting how little was known about the cause of heat prostration, but here were the leading theories:.

#1 - Workers were weakened by their poor diets: Meals consisted of doughnuts and coffee in the morning and soup in the evening. This diet regime was thought to impair their systems and lead to heat-induced problems.

#2 - Workers were eating too much food: Hoover Dam construction workers could eat as much as they wanted at the mess tent. Overeating was thought to make it difficult to perform manual labor in the heat.

#3 - Drinking water on the job. Many workers thought that consuming water led to heat prostration.

The number of injuries and deaths from heat prostration alarmed the company. Management sought help from Harvard University’s Fatigue Laboratory in 1932. After visiting the job site, the Harvard investigators quickly identified the problem: the workers were dehydrated and not drinking enough water. The Six Companies immediately provided more water stations and encouraged consumption by workers.

Construction companies are now mandated by OSHA to provide water to their workers. The concept is simple; however, implementing it on the job site is not easy. You can lead workers to water, but you can’t make them stay hydrated.

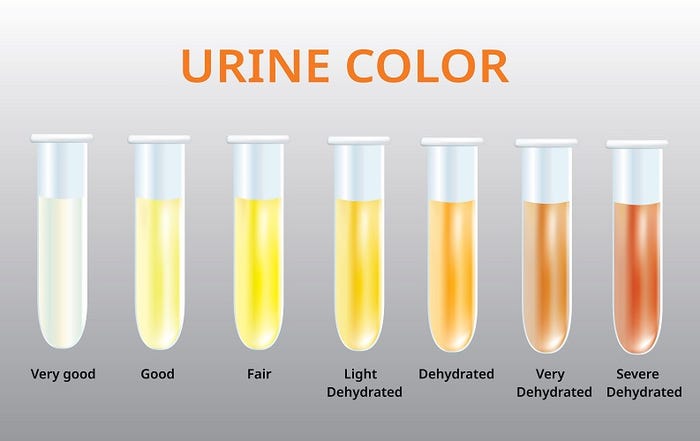

A recent article about construction in Mongolia is a reminder of the problem of workers not drinking enough water. Mongolia is building a copper mine in the Gobi Desert with low humidity, extreme heat in summer, and extreme cold in the winter. Workers are instructed each day to examine their urine color to determine if they are hydrated.

The critical concept for workers to understand is that they must continually monitor themselves for dehydration. Each person is different and needs to take responsibility for their health. Despite the scientific evidence, some myths are still believed, such as the only reason to visit the water cooler is to chat about sports and waste time. These jokes may be relatively innocent, but they overlook the water cooler’s vital role in preventing dehydration.

Another fallacy is that real men don’t take water breaks, which I first heard as a freshman in high school from my football coach. This advice could have been deadly. Sadly, the concept is still prevalent. Some workers and managers think water breaks are for sissies and discourage what they consider nonproductive rest periods. As was evident on the Hoover Dam construction site, water breaks keep the workforce productive and healthy. As marathoners have proven, water is necessary to keep up strength and finish the race. The same is valid on the construction site.

Another myth is that your body will recognize the need for water. When I was in Saudi Arabia, I was responsible for inspecting several building sites during the summer when temperatures routinely exceeded 110. I would stop for a break and did not feel thirsty until I drank my first cup of water. Then I would need to drink several more cups of water. This scenario led to the realization that I could not trust my body to recognize dehydration, so I developed a habit of regularly drinking water.

The common-sense solution to dehydration was first articulated by Harvard researchers and the Hoover Dam construction managers. Their discovery is the reason that water coolers are on all of our job sites today and that workers are expected to, and should, take water breaks.

Luke M. Snell is a concrete historian and Emeritus Professor at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. He has traveled the world promoting the certification programs of the American Concrete Institute. This article was previously published by the Arizona Contractor and Community.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like