Throughout recorded history, fibers have been used in construction materials to provide strength and reduce shrinkage cracking.

July 2, 2021

Luke M. Snell and Clifford N. MacDonald

The use of fibers in concrete may seem to be a twentieth-century development with a variety of fiber shapes and materials now available. But fiber use has a humble beginning that goes back centuries as our ancestors tried to improve their building materials.

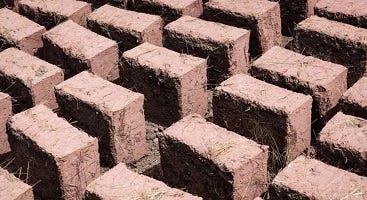

Sun-dried bricks reinforced with straw

One of the first man-made building materials was the sun-dried brick. To make these bricks, people would gather clay (adding water if necessary) so they could place the mixture into a mold. A typical mold would create a brick about 4 x 8 x 12 inches, weighing about 25 pounds. After the brick was formed and initially dried, it would be removed from the mold and dried in the sun. The drying step took several days and the bricks needed to be turned several time so they would have uniform drying. But, as clay dries (without any fibers) it experiences a great deal of shrinkage and cracking. If this cracking could not be eliminated, the bricks would be functionally useless. This led to the development of the first fibers—straw. The straw bridges or reinforces the cracks and holds the clay brick together as it dries. The first known use of this method was in the city of Jericho in 9000 BC.

A publication by the US Department of Agriculture (Adobe or Sun-Dried Brick for Farm Buildings, 1934), recommended about one pound of straw per brick. The exact amount of straw, however, depends on the shrinkage of the clay. The USDA recommends that one should experiment with the quantity of straw necessary to produce a crack-free brick and provides some hints on how to make a successful brick:

Either straw or hay can be used.

Use short pieces.

Make sure the straw or hay is well distributed throughout the brick.

Straw or hay with horse manure is preferred.

Probably the best-known tale about brick-making comes from the Biblical story of Exodus. The workers had to harvest their own fibers (straw) but still make the same number of sun-dried bricks as before. The workers considered this to be unfair and after intense negotiations (and several plagues), the Exodus from Egypt began.

Sun-dried bricks are still widely used in developing countries especially in hot dry areas. These bricks are easy to make, inexpensive, and provide a comfortable living space that is relatively cool.

Horsehair in lime plaster

Lime plaster was first used over 8000 years ago to cover walls in modern day Jordan. The plaster helps to seal the wall and provides excellent sound and temperature insulation. Unlike mud plaster, lime plaster was much more permanent. Some extra benefits were that the plaster had a high pH that inhibited surface mold from forming and the plaster could be easily painted or decorated.

The procedures developed in the U.S. to plaster a wall use lath and studs to form a lattice. This allows the plaster to ooze thorough the lath creating a mechanical bond that holds the plaster to the wall. The plaster itself has little strength, thus the studs and lath take the structural loads plus support the plaster wall.

Traditionally, plaster was made with quicklime, aggregates, water, and animal hair as the fiber. The animal hairs were added to lime plaster to help control the shrinkage and to hold the mixture together. Although it is called horsehair plaster, many other animal hairs were commonly used. According to one source, ox hair was superior to horsehair fibers however there were no supporting reasons. That source also recommended a 0.1% dosage of the animal hairs by weight of plaster.

Surprisingly, animal hair is still available for purchase. We suspect it is primarily used for those doing renovation work on historical buildings that want to reproduce the same materials that were used in the original construction.

A plaster wall would be installed with two to three coatings with a drying time of about a week between. Thus, horsehair plaster is labor intensive, requiring about a month to complete a wall. As new materials and construction techniques developed (especially drywall and gypsum plaster), horsehair plaster fell out of favor after World War II.

Asbestos fibers in concrete

Asbestos is a fibrous rock that first appeared to be an excellent choice as a fiber for concrete. It was used in ancient times to reinforce and prevent cracking in ceramic pottery. Asbestos is abundant and easy to mine, thus making it inexpensive. Using it as a fiber in concrete appeared to be logical. It also had additional attractive properties in that it was fire resistant. This made it ideal to use for insulation, roofing, siding, fire-resistant boards, and shingles. The use of asbestos as fibers for these products started in the late 1800s and was commonly used in many post World War II construction projects.

One industry that embraced using fiber was the precast concrete pipe industry. Asbestos concrete pipe was lightweight, had a low coefficient of friction, and was resistant to corrosion. The first asbestos concrete pipes were installed in 1930 and this was widely used until 1980.

Unfortunately, asbestos had a dark side. The fibers have been shown to cause an increased risk of cancer for anyone that handles or works with it. For that reason, the use of asbestos as fiber in concrete fell out of favor and in most places was outright prohibited.

The benefits that fiber provide to concrete was well recognized and led to research on safe effective fibers that could be easily added to the concrete mixture. As a result, today we have many types and shapes of fibers. These newer fibers basically do the same things as fibers from the past in controlling cracking, holding the concrete together, and generally improving performance and durability of concrete.

Luke M. Snell is a concrete historian and Emeritus Professor at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville; Clifford N. MacDonald is a concrete consultant for fiber-reinforced concrete.

You May Also Like